Tuesday, 20 December 2011

Switched On Santa?

Why are there no really good Christmas disco recordings? There are plenty of standard Holiday songs done in a 'disco' style, all jingling hi-hat, swooping strings and soft-pedalled wah-wah guitar under breathy choral voices, but there's no killer Xmas disco floor-filler. It's not as if there was no precedent, of course. A Christmas Gift For You, released in 1963 became an instant gold standard by which all other Holidays-themed soul records would be judged. Released in mono, Spector's trademark wall-of-sound featuring a band, horns, strings and backing singers complemented by constantly jingling bells, as Ronnie Bennett (later Spector), Darlene Love and Dolores 'La La' Brooks sing like debauched angelic hosts on top of the mad genius of sound's musical Christmas tree.

Just like previous albums by Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby and Doris Day (to name but three of many, many more), Spector's album includes standard seasonal songs, the oldest of which is Silent Night (written in 1818) credited to Phil Spector and Artists. There's also a version of White Christmas, of course, sung by Darlene Love, who gets the lead vocal on the only 'new' song, written with and for Spector by Ellie Greenwich and Jeff Barry, Christmas (Baby Please Come Home). It's this song which perhaps best epitomises why there's never been a great disco Christmas song.

Like Blane and Martin's Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas or Irving Berlin's White Christmas, Christmas (Baby Please Come Home) is almost a blues song. Full of longing, it's a sung-through wish for something that money cannot buy; love and companionship at what is meant to be the most spiritual time of the year (at least in the Christian calendar). How does that translate to disco? It can't.

Disco is the ultimate good-time, high-energy dance music, created to get people moving and not thinking. Slow disco numbers are as much about desire and need as uptempo disco numbers, where the beat has to be felt before the emotion and substitute sex for love. Christmas is a time for reflection and contemplation, both of which are to be found in the best Christmas songs. Even those songs which engage with the rampant materialism of the 20th century, such as Santa Claus Is Coming To Town, do so with a plea to consider life and its consequences ('He knows when you've been good or bad').

Crass attempts to earn a Holiday dollar by harnessing traditional songs of the season to the hottest sound of the day fail when those involved fail to understand that the singer—or arranger—needs to embody the sense and meaning of the song in their performance. While there are thousands of people for whom the Christmas Disco album holds fond memories, that is more because of their fanciful recollection of past family gatherings than the quality of the music on the album. The recordings having been created by session musicians in Nashville and sold around the world as anonymous season songs, they have surfaced at regular intervals since the early 1970s under different titles.

The Mistletoe Christmas Band's Christmas Album of 1971 was also released the same year as Switched On Christmas by TheHit Crew as Disco Noel by The Mistletoe Christmas Band and by Mirror Image. It later appeared titled Yuletide Disco by Mirror Image, and Christmas Disco Party by DJ Santa & The Dance Squad. Whatever it's called though, it all sounds like the kind of thing best heard in a crowded mall or a working elevator. Similarly, The Salsoul Orchestra's Christmas Jollies album is mostly musical slush, with only Sleigh Bells standing out as being worth tapping a toe to.

Following Spector's lead, somewhat inevitably, Berry Gordy produced many Christmas records by his stable of soul superstars, one of the best being the Jackson 5's 1970 version of the 1847-written Up On The House Top, on which the bouncy pre-pubescent Michael manages to mix some of the zaniness of Huey 'Piano' Smith with his pure pop freshness. The Supremes' Merry Christmas album isn't exactly up to the standard of The Ronettes seasonal offerings, but Diana Ross' voice has the right edge of longing and heartbreak in it to make the slower numbers work.

While there ain't no good disco songs worth adding to a Christmas playlist, there are still plenty of decent recordings worth spinning which will get people up cutting a rug—or crying a river. James Brown's Santa Claus Go Straight To The Ghetto, Otis Redding's Merry Christmas Baby, R Kelly's Merry Christmas, Stevie Wonder's That's What Christmas Means To Me, Marvin Gaye's (live) Christmas Song, Ike & Tina Turner's Merry Christmas Baby (or the Etta James version) and the definitive version of This Christmas by The Whispers all do it for the Morgan household.

Merry Christmas, wherever you are.

Monday, 12 December 2011

Frank and Gaga

Although he's no longer with us, Frank Sinatra (who would have celebrated his 96th birthday today, December 12) still casts a long shadow over the world of popular song. Although it's been 13 years since he passed, the man who had teenagers screaming at him a decade before Elvis (and two before the Beatles) continues to sell millions of CDs, capturing millions of views on youtube and prompting cores of imitators to try out versions of his back catalogue. Consider that Rod Stewart's last four albums, The Great American SongbookI-IV, have been his best-selling releases since the early 1970s, and they include almost solely songs made familiar by Frank. At the end of last month the rumours of Martin Scorcese's long mooted Sinatra biopic about to shoot resurfaced, with Di Caprio rumoured to be playing Frank. Having already made films about Dylan, a Beatle (George Harrison), the Stones and a history of sorts of the Blues, the Goodfellas, Casino and Gangs of New York director is apparently ready to begin retelling the life of the 20th century's most compelling and interesting performer.

Meanwhile, in imitation of Sinatra's Duets album of 1993, Tony Bennett released Duets in 2006, and just as Sinatra issued Duets II (1994), so Tony has issued his Duets II, on September 20 last. Like the first Sinatra release—which was universally slammed by critics at the time of release—Bennett's new album opens with a version of The Lady Is A Tramp. Lady Gaga's contribution to the song makes it undoubtedly the highlight of the album, and suggests that she and Frank might have tackled that, or any other song, brilliantly together. Her performance on the Bennett version uses vocal twitches and comic exaggerations ("Oimins and poils") that were first introduced into performances of classic American songs by Frank. Tony has always been a fine, strong vocalist, but he's always been strictly formal, and made his name as a belter rather than a song stylist—a term almost invented for Sinatra (the original version of the song, in Pal Joey, can be seen here).

In the accompanying promo film for Lady Is A Tramp, Gaga is dressed and coifed like Marilyn, and seems to have been watching both Frank and Anita O'Day performing in the car on her way to the studio. In her Tom Ford 'designed' black lace dress and a green bob, Gaga lifts the song way above the pedestrian level of many of the other tracks on Bennett's Duets II.

Sinatra's choice of Luther Vandross as duettist on his version of the song reflects perhaps Frank's regard for great vocalists above the merely popular. With the marked exception of the execrable Bono, Frank's Duets album is packed with fantastic singers, among them Barbra, Aretha, Liza, Anita, Charles Aznavour and Tony Bennett. (Tony also called in Barbra for his own first Duets release as well as, bizarrely, Bono.) The inclusion of Luther on Sinatra's Lady Is A Tramp, with it's smooth, soulful tones, reminds us that throughout his career, Frank often adapted well to new musical styles, as long as the song was good enough. In 1977 he re-recorded versions of Night And Day and All Or Nothing At All in an orchestral-disco mode, with the jazz guitarist Joe Beck as producer, and they're great.

Bennett's Duets II has also earned press because it includes a last recording by Amy Winehouse, on a version of Body & Soul. The song was possibly chosen because of its association with Billie Holiday, with whom Winehouse was most often compared. The video accompanying the recording lacks the wit and fun of Gaga's, but perhaps that's to be expected. Frank's late-1950s duet with Dinah Shore is much more fun to watch.

Frank enjoyed duetting with people throughout his career. His radio appearances in the 1940s with the incomparable Jimmy Durante are both hilarious and they swing. The Rat Pack nights are correctly regarded as being legendary and every recording is worth listening to more than once. Even when chasing a quick dollar Frank raised the standards of the pop genre. He gave daughter Nancy a huge hike in her career when he recorded a duet of Something Stupid in 1967 (earning himself another #1 hit). Compare that though, with this, recorded the same year; Frank's TV special duet with Ella Fitzgerald on a version of the fabulous Little Anthony & The Imperials song, Goin' Out Of My Head.

Frank's duet with Ella on The Lady Is A Tramp from the same show offers us both performers still at their performing peak, despite both being middle-aged. As the song progresses they can clearly be seen getting into the groove, digging what they're doing, knowing that it's something special. There's something of that to be seen in Gaga's performance with a the decidedly old-aged Bennett on their Lady Is A Tramp, and suggests that, had timing been right, Lady Gaga and the Chairman of the Board could have made a great team.

Wednesday, 30 November 2011

Pink Floyd's Discoballs

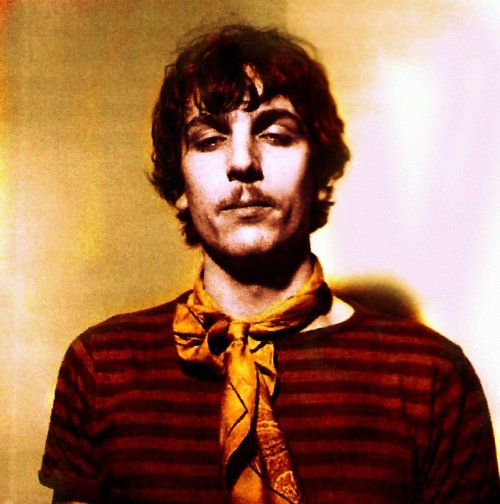

When Pink Floyd started out in the mid-1960s they were a disco band. Or at least, they played at what passed for discos in London in 1966. The now infamous UFO Club became the scene for some of the most mind-expanding discos of the era, and the Floyd were almost the house band. The Floyd's version of Interstellar Overdrive was a guaranteed floor-filler, and unlike most of the usual dance hits of the day which usually comprised less than three minutes of hip-shaking, butt-wriggling, soft-shoe shuffling grooving, it went on and on until dancers were properly done in. Floyd's main man of the time, Syd Barrett, according to a fantastic recent book titled 'Barrett', had been grooving on old blues and R&B numbers for a while before forming the band in Cambridge.

Now, the idea of the Floyd as a disco band will doubtless annoy a lot of their more serious prog-infected fans, but given that the band had only two hit singles in their time worth mentioning, and both were disco-driven, should make even them stop and feel the groove. In 1977 a French music composer named Gabriel Yared was definitely feeling the Floyd disco groove when he arranged, co-produced and played on Discoballs, A Tribute to Pink Floyd, crediting it to the fictional 'band' Rosebud. The cinematic reference in the name reflects Yared's real passion, which is for movie soundtrack composing. He's better known as the composer of the soundtrack score for Betty Blue and The English Patient.

Discoballs starts at the beginning of the Floyd's career with contemporary disco reworkings of Interstellar Overdrive and 'Arnold Layne', before moving onto a great version of Money from 'Dark Side Of The Moon'. Improbable as it sounds, Rosebud's version was a club hit in the US and Europe, it having benefited from the previous success of their version of Have A Cigar which had been an an even bigger dance hit.

Doubtless impressed with Yared's work on their catalogue, the Floyd adapted a disco beat to the recording of the one truly international hit single that they enjoyed in their career: Released in late 1979/early 1980, Another Brick In The Wall Part 2, taken from The Wall became an unlikely hit, and was played in discos around the world. For any doubters out there, take a look at this perfect mash-up of Brick and the Bee Gees' Stayin' Alive. Can you see the joins?

Of course, by the end of the 1970s everyone was jumping on the disco revolving ball in search of a hit, and that included some unlikely prog-rock heroes. Jannick Top, the bass player on Discoballs had spent the previous ten years working with weirdo French space-prog act Magma, for instance. The Grateful Dead took to wah-wah and hi-hat on Shakedown Street in 1978. However, perhaps the most surprising disco convert was Keith Emerson, formerly keyboard player with The Nice and ELP. Emerson was arguably one of the prime movers in the development of prog rock — take a look at him here in 1968 with The Nice (Warning: it's only 5.44 min long, but feels like 15:44).

As one third of the ludicrously pompous, over-blown and self-indulgent ELP (find your own links, I'm not going to make anyone suffer Tarkus or Brain Salad Surgery), Emerson constructed faux symphonies on his over-heating Hammond organ, and live performances by ELP went on for so long that venue owners started charging them monthly rents. If asked to nominate any prog musician who would have been a fully signed-up member of the odious 'disco sucks' movement, I would have chosen Emerson. Which makes the discovery of this all the more surprising; It's Emerson's version of the great Chicago original, I'm A Man and was released as a single taken from his soundtrack to the Sly Stallone movie, Nighthawks.

Nighthawks, which was originally going to be French Connection Part III until Gene Hackman pulled out of the project, is a nice period piece (1981), as you can tell from Sly's facial hair. There's a couple of great scenes in discos, one of which features people dancing the the Rolling Stones' Brown Sugar. This clip uses the Emerson album track, 'Nighthawking' though. But it's Emerson's I'm A Man that's the stand-out track. Watching the Chicago Transit Authority (as they were still called) perform their song live in 1969, you can hear why Emerson considered it easy to adapt for a disco treatment. Watching the Floyd perform Money live in 1973, or hearing them play Have A Cigar in 1975 isn't exactly a disco experience, though. Which makes Yared's disco vision even more remarkable.

Since Rosebud's Discoballs cast a shimmering light on the disco potential of Floyd, there have been other producers and musicians to do likewise.On Floyd: A Chillout Experience Lazy put Money into a bossa nova beat, along with several other Floyd tracks. Of course, chillout was where the Floyd went to after Syd left, and it's no surprise that acts like The Orb took inspiration from them, or that Feeling Floyd came into being; here they are making out on the Floyd's tribute to Syd, Shine On You Crazy Diamond. Not that it's anywhere near disco. However, this very fine and anonymous mix of Money, which claims to feature the voice of Sharon Stone, uses Laurence Olivier and Bob Hoskyns from Paul Hardcastle's Just For Money (plus an odd photograph) to create an oddly danceable version with extra meaning.

Now, the idea of the Floyd as a disco band will doubtless annoy a lot of their more serious prog-infected fans, but given that the band had only two hit singles in their time worth mentioning, and both were disco-driven, should make even them stop and feel the groove. In 1977 a French music composer named Gabriel Yared was definitely feeling the Floyd disco groove when he arranged, co-produced and played on Discoballs, A Tribute to Pink Floyd, crediting it to the fictional 'band' Rosebud. The cinematic reference in the name reflects Yared's real passion, which is for movie soundtrack composing. He's better known as the composer of the soundtrack score for Betty Blue and The English Patient.

Discoballs starts at the beginning of the Floyd's career with contemporary disco reworkings of Interstellar Overdrive and 'Arnold Layne', before moving onto a great version of Money from 'Dark Side Of The Moon'. Improbable as it sounds, Rosebud's version was a club hit in the US and Europe, it having benefited from the previous success of their version of Have A Cigar which had been an an even bigger dance hit.

Doubtless impressed with Yared's work on their catalogue, the Floyd adapted a disco beat to the recording of the one truly international hit single that they enjoyed in their career: Released in late 1979/early 1980, Another Brick In The Wall Part 2, taken from The Wall became an unlikely hit, and was played in discos around the world. For any doubters out there, take a look at this perfect mash-up of Brick and the Bee Gees' Stayin' Alive. Can you see the joins?

Of course, by the end of the 1970s everyone was jumping on the disco revolving ball in search of a hit, and that included some unlikely prog-rock heroes. Jannick Top, the bass player on Discoballs had spent the previous ten years working with weirdo French space-prog act Magma, for instance. The Grateful Dead took to wah-wah and hi-hat on Shakedown Street in 1978. However, perhaps the most surprising disco convert was Keith Emerson, formerly keyboard player with The Nice and ELP. Emerson was arguably one of the prime movers in the development of prog rock — take a look at him here in 1968 with The Nice (Warning: it's only 5.44 min long, but feels like 15:44).

As one third of the ludicrously pompous, over-blown and self-indulgent ELP (find your own links, I'm not going to make anyone suffer Tarkus or Brain Salad Surgery), Emerson constructed faux symphonies on his over-heating Hammond organ, and live performances by ELP went on for so long that venue owners started charging them monthly rents. If asked to nominate any prog musician who would have been a fully signed-up member of the odious 'disco sucks' movement, I would have chosen Emerson. Which makes the discovery of this all the more surprising; It's Emerson's version of the great Chicago original, I'm A Man and was released as a single taken from his soundtrack to the Sly Stallone movie, Nighthawks.

Nighthawks, which was originally going to be French Connection Part III until Gene Hackman pulled out of the project, is a nice period piece (1981), as you can tell from Sly's facial hair. There's a couple of great scenes in discos, one of which features people dancing the the Rolling Stones' Brown Sugar. This clip uses the Emerson album track, 'Nighthawking' though. But it's Emerson's I'm A Man that's the stand-out track. Watching the Chicago Transit Authority (as they were still called) perform their song live in 1969, you can hear why Emerson considered it easy to adapt for a disco treatment. Watching the Floyd perform Money live in 1973, or hearing them play Have A Cigar in 1975 isn't exactly a disco experience, though. Which makes Yared's disco vision even more remarkable.

Since Rosebud's Discoballs cast a shimmering light on the disco potential of Floyd, there have been other producers and musicians to do likewise.On Floyd: A Chillout Experience Lazy put Money into a bossa nova beat, along with several other Floyd tracks. Of course, chillout was where the Floyd went to after Syd left, and it's no surprise that acts like The Orb took inspiration from them, or that Feeling Floyd came into being; here they are making out on the Floyd's tribute to Syd, Shine On You Crazy Diamond. Not that it's anywhere near disco. However, this very fine and anonymous mix of Money, which claims to feature the voice of Sharon Stone, uses Laurence Olivier and Bob Hoskyns from Paul Hardcastle's Just For Money (plus an odd photograph) to create an oddly danceable version with extra meaning.

Monday, 12 September 2011

Is It All Over My Face?

As the summer turns to Fall and memories of loss and regret crowd in with lowering skies, shortened days and dropping temperatures, music from a past life helps to gain some kind of perspective on what has been, and may still be. Classic disco tracks have the power to be both nostalgic and strangely contemporary. Spinning vinyl versions of records bought decades ago is pure nostalgia, evoking in the feel and smell of the record instant memories of where each click, jump or stick will be, and how they were caused. Clicking on an old favourite in iTunes or Spotify has a different effect, though. Being clear, clean and compressed to a clinical EQ which works to both make it sound like it's 2011, and remind us of the thirty five years since the song first made our body groove.

Candi Staton's Young Hearts Run Free was—is—one of my favourite disco tunes. Whenever it was spun in the disco where I spent every other night during the long, hot summer of 1976, the hairs on the back of my neck would raise and my feet would move to the ever-crowded dancefloor, preferably with the then love of my life alongside me. Candi's regret-filled voice sang a warning that was undoubtedly heartfelt, but almost impossible to heed because you couldn't believe that she meant it. She was so hung up with her man that no matter how bad things were—and by all accounts things between Candi and her second husband, the blind singer Clarence Carter, were pretty bad—there was something compelling about the experience that gave her voice a timbre impossible to impersonate; the sound of pure heartbreak.

While the song was not 'written' by Candi, the experience which informs it is all hers. Songwriter and producer David B Crawford was a close friend to the singer and she'd told him all the terrible detail of her abusive relationship. In return he'd written Young Hearts for her, and it proved to be the biggest hit that either of them would enjoy.

The message of 'save yourself even if it is too late for me' added to a wave of disco songs sung (and sometimes written) by female artists who, like Candi (born 1940), had lived a life before becoming stars. Shirley Brown's Woman To Woman is structured as a phone call between a wronged wife and a mistress, and is remarkably free of threat, warning or revenge. Shirley simply wants to let her rival know, 'woman to woman' that she loves him enough to do what it takes in order to keep him. The lack of rancour in the lyric and way it's sung keeps the song from being a masochistic submission to chauvinist repression. Not that standing by your man was a dominant trend for post-feminist disco women. Two years after Young Hearts had made her an international star, Candi had another hit which referenced that song; Victim ('of the very songs I sing'). In the 1978 number, also written by David B Crawford, she laments falling for another man who leaves her for another woman, and noting that 'if my advice is good for others/it's good to be good for me', but ending with the sentiment that 'I'm lucky if I can break these chains'. However, the self-accusatory chanting of 'victim' works as well as a reproach against depending on any man as the chorus of Young Hearts Run Free.

Also in 1978, Chaka Khan became a solo star singing Ashford and Simpson's I'm Every Woman, which while it depends on a traditional male-female sexual dependency, stridently makes the point that one woman is every woman—or should be—and all that any one man could want or need.

In October 1978 the great disco anthem for wronged women was released; I Will Survive was Gloria Gaynor's second huge international hit (after Never Can Say Goodbye in 1974), and became the one for which she is still remembered. Written by Freddie Perren who'd already created hit disco numbers for the Jackson 5, Tavares and the Sylvers, and Dino Fakaris, with whom he'd create hits for Peaches And Herb, I Will Survive takes the form of a first-person address by a women to the man who's wronged her by dumping her and turning up unannounced at her place. The chorus' assertion of self-determination and independence has unsurprisingly carried through the decades and remains as popular as it ever was.

It's surprising that the emphasis on 'love' between a woman and a man persisted in disco lyrics until well into the 1980s, since the scene was driven by lust and instant gratification. Even the great Weather Girls' smash hit It's Raining Men (1982, though written in 1979 by Pauls Jabara and Shaffer) speaks of angels arranging things so that every single girl can find her 'perfect man'. Not that the song was interpreted in a literal sense by the people who danced to the extended mixes in discos around the world.

In truth, as the new decade dawned a less romantic and more realistic lyric was being used in hardcore disco numbers. Loose Joints' fabulous Is It All Over My Face (1980, Arthur Russell and Steve D'Acquisto) is a stripped down funk workout—in it's Larry Levan remix—with minimalist lyrics sung by a foreign-sounding anonymous female (although the first version used three male voices), the main refrain of which 'Is it all over my face' is lyrically linked to 'how I love dancing'. But everyone 'knows' that the 'it' refers to something more substantial than a look, something linked to 'love' as biological matter. It's a deconstructed hymn to the sexual act, non-gender specific and physically compelling.

Is It All Over My Face lacks the emotional complexity of Young Hearts Run Free, even if contains within it the same message and perfectly captures the mood of the coming decade of materialistic desire and consumer greed.

Candi Staton's Young Hearts Run Free was—is—one of my favourite disco tunes. Whenever it was spun in the disco where I spent every other night during the long, hot summer of 1976, the hairs on the back of my neck would raise and my feet would move to the ever-crowded dancefloor, preferably with the then love of my life alongside me. Candi's regret-filled voice sang a warning that was undoubtedly heartfelt, but almost impossible to heed because you couldn't believe that she meant it. She was so hung up with her man that no matter how bad things were—and by all accounts things between Candi and her second husband, the blind singer Clarence Carter, were pretty bad—there was something compelling about the experience that gave her voice a timbre impossible to impersonate; the sound of pure heartbreak.

While the song was not 'written' by Candi, the experience which informs it is all hers. Songwriter and producer David B Crawford was a close friend to the singer and she'd told him all the terrible detail of her abusive relationship. In return he'd written Young Hearts for her, and it proved to be the biggest hit that either of them would enjoy.

The message of 'save yourself even if it is too late for me' added to a wave of disco songs sung (and sometimes written) by female artists who, like Candi (born 1940), had lived a life before becoming stars. Shirley Brown's Woman To Woman is structured as a phone call between a wronged wife and a mistress, and is remarkably free of threat, warning or revenge. Shirley simply wants to let her rival know, 'woman to woman' that she loves him enough to do what it takes in order to keep him. The lack of rancour in the lyric and way it's sung keeps the song from being a masochistic submission to chauvinist repression. Not that standing by your man was a dominant trend for post-feminist disco women. Two years after Young Hearts had made her an international star, Candi had another hit which referenced that song; Victim ('of the very songs I sing'). In the 1978 number, also written by David B Crawford, she laments falling for another man who leaves her for another woman, and noting that 'if my advice is good for others/it's good to be good for me', but ending with the sentiment that 'I'm lucky if I can break these chains'. However, the self-accusatory chanting of 'victim' works as well as a reproach against depending on any man as the chorus of Young Hearts Run Free.

Also in 1978, Chaka Khan became a solo star singing Ashford and Simpson's I'm Every Woman, which while it depends on a traditional male-female sexual dependency, stridently makes the point that one woman is every woman—or should be—and all that any one man could want or need.

In October 1978 the great disco anthem for wronged women was released; I Will Survive was Gloria Gaynor's second huge international hit (after Never Can Say Goodbye in 1974), and became the one for which she is still remembered. Written by Freddie Perren who'd already created hit disco numbers for the Jackson 5, Tavares and the Sylvers, and Dino Fakaris, with whom he'd create hits for Peaches And Herb, I Will Survive takes the form of a first-person address by a women to the man who's wronged her by dumping her and turning up unannounced at her place. The chorus' assertion of self-determination and independence has unsurprisingly carried through the decades and remains as popular as it ever was.

It's surprising that the emphasis on 'love' between a woman and a man persisted in disco lyrics until well into the 1980s, since the scene was driven by lust and instant gratification. Even the great Weather Girls' smash hit It's Raining Men (1982, though written in 1979 by Pauls Jabara and Shaffer) speaks of angels arranging things so that every single girl can find her 'perfect man'. Not that the song was interpreted in a literal sense by the people who danced to the extended mixes in discos around the world.

In truth, as the new decade dawned a less romantic and more realistic lyric was being used in hardcore disco numbers. Loose Joints' fabulous Is It All Over My Face (1980, Arthur Russell and Steve D'Acquisto) is a stripped down funk workout—in it's Larry Levan remix—with minimalist lyrics sung by a foreign-sounding anonymous female (although the first version used three male voices), the main refrain of which 'Is it all over my face' is lyrically linked to 'how I love dancing'. But everyone 'knows' that the 'it' refers to something more substantial than a look, something linked to 'love' as biological matter. It's a deconstructed hymn to the sexual act, non-gender specific and physically compelling.

Is It All Over My Face lacks the emotional complexity of Young Hearts Run Free, even if contains within it the same message and perfectly captures the mood of the coming decade of materialistic desire and consumer greed.

Monday, 29 August 2011

Tell Him I'm Not Home

Being out of the reach of any telecommunication device for a week feels incredibly indulgent in this era of constant contact and interminable twitter. It can also create a nostalgic yearning for the days when a telephone was not a mobile device, but rather tied its owner to a place and provided them with an air of mystery which meant that the owner of a number such as Beechwood 45789, or 634 5789, could choose to not be 'in' when that phone rings right off the wall.

Soul song writers of the early 1960s understood the telephone as a device that could be used as a come-on or a rejection, encapsulating a world of wanting in the miles of wire that linked one person to the object of their desire. Songs that revolved around the telephone generally played on the pleading aspect of that simple phrase, 'Call Me'. Lucky guys or girls could get a 'private number' while unlucky callers could ask an 'Operator' to connect them with a reluctant lover, although as the great Chuck Jackson understood, you could just as easily get the message, 'Tell Him I'm Not Home'.

Chris Montez and Astrud Gilberto bossa-nova'd their separate versions of the same 'Call Me' written by Tony Hatch in 1965 (Astrud liked 'phones), while Aretha Franklin and Al Green slow soul-stirred their different, self-penned songs of the same title in the early 1970s, but probably the best-known disco song demanding a telephone chat was co-written by Giorgio Moroder and Debbie Harry. Blondie's 'Call Me' came about because Donna Summer didn't want to work on a song for a 1980 movie titled American Gigolo (she was a devout Christian, and was already regretting her moaning performance of 'Love To Love You Baby'). Donna's loss was Debbie's gain, and the song hit the top of the charts around the world. Blondie had demonstrated their penchant for telephonic communication in 1978 with 'Hanging On The Telephone', of course.

Like all the previously mentioned songs, Blondie's 'Call Me' is a cry to a distant lover to get in touch, albeit expressed to a slightly more uptempo backing than Aretha, Al, Shirley Brown ('Woman To Woman'), Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes ('Miss You'), Bootsy Collins ('What's A Telephone Bill?'), or Peaches & Herb ('Reunited')—Tavares' 'Whodunnit' mentions a telephone, but only in order to "call Sherlock Holmes". It wasn't until the 80s that telephone songs really became dance songs. Sadly, Anita Ward's 'Ring My Bell' has no telephone references in the lyrics.

In 1981 Luther Vandross' debut single (and album title track) 'Never Too Much' added bpm to the telephone's role as instrument of heartbreak and desire. Unfortunately Village People (Mk II) kept the bpm but made the telephone an object of ridicule in 1985 with 'Sex Over The Phone', but thankfully Pet Shop Boys made the telephone an instrument of isolation and abandonment with plenty of bpm in 'Left To My Own Devices' in 1987. More recently of course Lady Gaga (and Beyoncé) have made 'Telephone'. Despite the advent of the cell (mobile) telephone and its promise of 24-hour access, Gaga's lack of receptivity 'in the club' is a negation of human connectivity that echoes Chuck Jackson's 'Tell Him I'm Not Here'. Five decades on and the telephone is still a symbol of imagined, desired, virtual love for something we can't have. So let's dance anyway.

P.S. Anyone got any other telephone-related songs to add to this?

Soul song writers of the early 1960s understood the telephone as a device that could be used as a come-on or a rejection, encapsulating a world of wanting in the miles of wire that linked one person to the object of their desire. Songs that revolved around the telephone generally played on the pleading aspect of that simple phrase, 'Call Me'. Lucky guys or girls could get a 'private number' while unlucky callers could ask an 'Operator' to connect them with a reluctant lover, although as the great Chuck Jackson understood, you could just as easily get the message, 'Tell Him I'm Not Home'.

Chris Montez and Astrud Gilberto bossa-nova'd their separate versions of the same 'Call Me' written by Tony Hatch in 1965 (Astrud liked 'phones), while Aretha Franklin and Al Green slow soul-stirred their different, self-penned songs of the same title in the early 1970s, but probably the best-known disco song demanding a telephone chat was co-written by Giorgio Moroder and Debbie Harry. Blondie's 'Call Me' came about because Donna Summer didn't want to work on a song for a 1980 movie titled American Gigolo (she was a devout Christian, and was already regretting her moaning performance of 'Love To Love You Baby'). Donna's loss was Debbie's gain, and the song hit the top of the charts around the world. Blondie had demonstrated their penchant for telephonic communication in 1978 with 'Hanging On The Telephone', of course.

Like all the previously mentioned songs, Blondie's 'Call Me' is a cry to a distant lover to get in touch, albeit expressed to a slightly more uptempo backing than Aretha, Al, Shirley Brown ('Woman To Woman'), Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes ('Miss You'), Bootsy Collins ('What's A Telephone Bill?'), or Peaches & Herb ('Reunited')—Tavares' 'Whodunnit' mentions a telephone, but only in order to "call Sherlock Holmes". It wasn't until the 80s that telephone songs really became dance songs. Sadly, Anita Ward's 'Ring My Bell' has no telephone references in the lyrics.

In 1981 Luther Vandross' debut single (and album title track) 'Never Too Much' added bpm to the telephone's role as instrument of heartbreak and desire. Unfortunately Village People (Mk II) kept the bpm but made the telephone an object of ridicule in 1985 with 'Sex Over The Phone', but thankfully Pet Shop Boys made the telephone an instrument of isolation and abandonment with plenty of bpm in 'Left To My Own Devices' in 1987. More recently of course Lady Gaga (and Beyoncé) have made 'Telephone'. Despite the advent of the cell (mobile) telephone and its promise of 24-hour access, Gaga's lack of receptivity 'in the club' is a negation of human connectivity that echoes Chuck Jackson's 'Tell Him I'm Not Here'. Five decades on and the telephone is still a symbol of imagined, desired, virtual love for something we can't have. So let's dance anyway.

P.S. Anyone got any other telephone-related songs to add to this?

Monday, 15 August 2011

Too Tight To Mention

The events of civil unrest in England last week have been dubbed the 'JD Riots' in some quarters, because crowds seemed to target that sportswear chain above all other stores. JD Sports sell brands usually promoted by sports and music superstars; Adidas, Nike, Vans etc. The chain was started by two Mancunians who spotted a trend among the young male working class of their area who bought leisure and sports brand clothing from catalogues or in upmarket London shops that were far from mainstream garb for young people in the 1980s. They were known as 'casuals' because of their love of clothing made by the likes of Fila, Ellesse, Lacoste and other similarly casual smart clothing brands apparently designed to grace golf courses, tennis courts and mob bosses across America. Casuals loved dancing, fighting and football, usually at the same time: social anthropologists can trace their roots back as far as Skinheads and Mods—all linked through music and clothes, two things which disco conflated perfectly for a brief period in the 1970s.

When British author Nik Cohn handed in a piece of fiction instead of journalism, titled Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night in 1975, it was so convincing to the editors at New York Magazine that they believed he'd actually been into the Odyssey disco in Queens. In fact, Cohn chickened out of entering the club and instead invented his story, achieving a realistic effect in great part due to the sartorial detail of the story (which went on to become Saturday Night Fever).

The original piece begins with the lines, 'Vincent was the very best dancer in Bay Ridge—the ultimate Face. He owned fourteen floral shirts, five suits, eight pairs of shoes, three overcoats, and had appeared on American Bandstand'. The definition of 'Face' came from Cohn's past as a Mod in London, part of a small scene which emerged around 1960 in which young men wore hand-made suits (paid for with wages saved up for as long as it took), button-down shirts and ties, Savile Row-inspired (if not made) velvet-collared Crombie overcoats and Bass Weejun loafers imported from America. The Mod with the sharpest suits and shiniest shoes was forever known as the Ace Face in the crowd. Mods preferred to dance only to American soul records of the pre-Beatles era, the kind of girl groups also favored by the Fab Four (who wore mock-Mod suits). Which is why it made sense to Cohn that any disco-obsessed dancer in New York in 1975 be as smartly dressed as he'd been.

|

| the site of the original Odyssey in Queens |

The Saturday night rituals ascribed to Vincent in Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night—the posing in the mirror, the imagining himself as Pacino or Lee Van Cleef, the hanging and posing with a posse of lesser 'Faces', strutting along the street in clothes too thin and exposing for the hard winter night—were repeated by real-life Vincents in every major Western city in the 1970s.

In Richard Price's Ladies' Man (1978), his central character Kenny Becker is Vincent only a few years older, living alone in Manhattan but just as obsessed with sex, soul and disco music (there's a great scene in the novel describing Kenny getting ready to go out for the night, he starts by 'dropping a Barry White and two James Browns on the machine', and carefully preps himself).

In his hugely successful debut novel The Wanderers (1974), Price had written what amounts to an autobiography about his time as a teenage member of a New York gang in 1963 (he was born in the Bronx in 1949). The novel (and movie, made in 1979) is full of music, all pre-Beatles doo-wop, soul and R&B. There's a scene at a private party in which the girls form a line and dance in formation to the Angels' My Boyfriend's Back, with moves self-choreographed just as much as Vincent's in Saturday Night Fever, and similar in many ways, too. The Wanderers wore a 'uniform' of baseball jackets, quiffs and tight jeans, Kenny favors 'pearl gray continental slacks, a thick wool hot pink turtleneck and my black velvet sports jacket'.

Clothes, music and Saturday nights have ever been a holy trinity for the working man in a modern Western free market capitalist state. As long as the man has a job, he is somebody in society. His wages are spent on making himself look and feel as good as any other wage slave. Mods worked for the weekend; working class Tories the lot of them. Vincent worked (in a paint store) for the weekend buzz he got from dancing, looking good and being watched. Kenny is proud of the money he makes in Ladies' Man (as a door-to-door salesman) but his life falls apart when he deliberately loss his job, and ends with him questioning his sexuality and his wholly uncertain future.

Last week's JD rioters have no job, have no dignity afforded by labor and their primary function as consumers has been denied them by that fact. Is it just bad luck got a hold of them?

Monday, 8 August 2011

Be For Real

Following the murder of Dr King in 1968, several American cities went up in flames as grief found vent in fury and destruction. It was as if people who believed in Martin Luther King's message of peaceful protest sensed the impossiblity in his dream and turned their anger on the physical world from which he'd been ripped. Huge swathes of America were resisting in 1968. Pro-civil rights, anti-war and anti-capitalist protests were many and frequent in Washington, New York, San Francisco, Chicago, Birmingham and all across the country. As the free market capitalist state matured from the middle of the century it inspired resistance in many parts of Western society, particularly among people who did not fit into designated roles created to help the functioning of the materialist orthodoxy. The arts became the successful media of heterodoxy and conveyor of a message of resistance.

The blues, rock 'n'roll, soul and disco music spread the anti-capitalist message with seductive beats and subversive message. It wasn't just 'underground' music which preached resistance, either. By 1968 even Tamla Motown had encouraged its pop superstar roster to record 'message' songs such as 'Love Child' by The Supremes, and the psychedelic 'Cloud Nine' by the Temptations. On the night following Dr King's murder of April 4, James Brown was called upon by the mayor of Boston to talk down expected rioters before performing a live televised concert. It worked and Boston was 'saved' from flames of indignation and resistance. In August that year he released 'Say It Loud—I'm Black And I'm Proud' and launched a raft of great early disco recordings in which black pride, anti-capitalist and pro-civil rights messages are forced home with a funky beat and honking horn sections.

The recent events in London reminded me of the anti-materialist revolution of the 1970s (which went on to include punks and post-punk funkers of the 1980s), but not in a good way. It's depressing to watch 'rioters' using the cover of an ostensibly legitimate protest at police and state repression in order to ransack stores for products which they can't afford to pay for. The looting is inevitable but the people risking their lives and liberty for shoddy shoes made by slave labor in China do so in order to either show off their swag, or sell it on eBay. Everything taken by looters should have been piled high on the police cars burning in the streets. Why is there no real questioning of the status quo going on here? The London rioters are not volubly questioning the ruling doctrine of capitalism, and in their pilfering they are acting in support of a value system which gives material goods precedence over dignity. The rioters who looted acted like customers who have, for no reason of their own, malfunctioned and are unable to carry out the only role for which they are trained; to consume. Their crimes however are nothing compared with the bankers, politicians, businessmen and strategists who ensure that the 'free market' orthodoxy persists even in the face of obvious evidence that it is failing.

Riots of the inner city areas in America in the 1960s and '70s, and in the inner city areas of England in the early 1980s saw destruction of the slums which people were forced to live in because of their economic inability. The result was a rebuilding of homes and a focussing on the problems faced by residents of those areas. Riots on retail streets such as those of yesterday will only see plans to exclude the economically distressed from those streets drawn up by owners of the retail outlets. We might see plans for the reduction in police budgets ripped up when businesses scared of losing income by forced closure bring pressure to bear on the government of England which no-one voted for. They'll need to increase 'security' in retail areas.

Sadly, any further exclusion from consuming for the rioters is likely to hurt far more than the erosion of civil rights or the National Health service which their 'government' is forcing through. What people need today is a renewal of the message from forty years back, a message which you can dance to.

As Teddy Pendergrass puts it in his spoken word riff in Be For Real; 'don't make your own brothers and sisters feel bad…as long as you live, as long as you with me; be for real'.

The blues, rock 'n'roll, soul and disco music spread the anti-capitalist message with seductive beats and subversive message. It wasn't just 'underground' music which preached resistance, either. By 1968 even Tamla Motown had encouraged its pop superstar roster to record 'message' songs such as 'Love Child' by The Supremes, and the psychedelic 'Cloud Nine' by the Temptations. On the night following Dr King's murder of April 4, James Brown was called upon by the mayor of Boston to talk down expected rioters before performing a live televised concert. It worked and Boston was 'saved' from flames of indignation and resistance. In August that year he released 'Say It Loud—I'm Black And I'm Proud' and launched a raft of great early disco recordings in which black pride, anti-capitalist and pro-civil rights messages are forced home with a funky beat and honking horn sections.

The recent events in London reminded me of the anti-materialist revolution of the 1970s (which went on to include punks and post-punk funkers of the 1980s), but not in a good way. It's depressing to watch 'rioters' using the cover of an ostensibly legitimate protest at police and state repression in order to ransack stores for products which they can't afford to pay for. The looting is inevitable but the people risking their lives and liberty for shoddy shoes made by slave labor in China do so in order to either show off their swag, or sell it on eBay. Everything taken by looters should have been piled high on the police cars burning in the streets. Why is there no real questioning of the status quo going on here? The London rioters are not volubly questioning the ruling doctrine of capitalism, and in their pilfering they are acting in support of a value system which gives material goods precedence over dignity. The rioters who looted acted like customers who have, for no reason of their own, malfunctioned and are unable to carry out the only role for which they are trained; to consume. Their crimes however are nothing compared with the bankers, politicians, businessmen and strategists who ensure that the 'free market' orthodoxy persists even in the face of obvious evidence that it is failing.

Riots of the inner city areas in America in the 1960s and '70s, and in the inner city areas of England in the early 1980s saw destruction of the slums which people were forced to live in because of their economic inability. The result was a rebuilding of homes and a focussing on the problems faced by residents of those areas. Riots on retail streets such as those of yesterday will only see plans to exclude the economically distressed from those streets drawn up by owners of the retail outlets. We might see plans for the reduction in police budgets ripped up when businesses scared of losing income by forced closure bring pressure to bear on the government of England which no-one voted for. They'll need to increase 'security' in retail areas.

Sadly, any further exclusion from consuming for the rioters is likely to hurt far more than the erosion of civil rights or the National Health service which their 'government' is forcing through. What people need today is a renewal of the message from forty years back, a message which you can dance to.

As Teddy Pendergrass puts it in his spoken word riff in Be For Real; 'don't make your own brothers and sisters feel bad…as long as you live, as long as you with me; be for real'.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)